The Basics of Linear Algebra (Part 2)

Hey! Welcome back. This is a continuation of the previous blog post I made, so make sure you’re familiar with the concepts I discuss there before you read this.

Last time we stopped at matrix multiplication. This time, we take the torch forward from there.

- Matrix to matrix multiplication

- Inverse of a matrix

- Identity matrix

- Transpose

- Broadcasting

- Hadamard product

- Trace

- Some special vectors and matrices

- Tensor

- Reality check

- Extra references

Matrix to matrix multiplication

So you know what happens when you multiply a matrix to a vector now. But what about one matrix multiplied by another? How does that work and what is it supposed to mean?

Short answer: Matrix to matrix multiplication is like a composition of functions, you apply one after the other.

Let’s look at the longer explanation now.

The intuition

So you know a matrix contains the locations of where the basis vectors land after we perform some transformation on the vector space, right?

Let’s take an example. Consider this matrix: \(\boldsymbol{A}=\begin{bmatrix}-1 & -1 \\ 1 & -1\end{bmatrix}\).

One can tell from a glance, applying this transformation to our default vector space (the one with \(\hat{i}\) and \(\hat{j}\)) will result in the basis vectors (i.e. \(\hat{i}\) and \(\hat{j}\)) landing on the positions \([-1,\ 1]\) and \([-1,\ -1]\) respectively.

But what if we want to apply another transformation to this already transformed space? What if we want to combine two transformations?

So let’s say we multiply \(\boldsymbol{A}\) to some vector \(\boldsymbol{v}=[1,\ 1]\). Here’s what would happen:

\[\begin{bmatrix}-1 & -1 \\ 1 & -1\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}1 \\ 1\end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix}-2 \\ 0\end{bmatrix}\]

And now we want to apply another transformation to \(\boldsymbol{v}\). What do we do?

We multiply it again with the corresponding matrix. Let’s assume we want to apply the transformation represented by the matrix \(\boldsymbol{B}=\begin{bmatrix}-1 & 1 \\ 0 & -2\end{bmatrix}\). Here’s what happens:

\[\begin{bmatrix}-1 & 1 \\ 0 & -2\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}-2 \\ 0\end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix}2 \\ 0\end{bmatrix}\]

So effectively, what we did is:

\[\begin{bmatrix}-1 & 1 \\ 0 & -2\end{bmatrix}\left(\begin{bmatrix}-1 & -1 \\ 1 & -1\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}1 \\ 1\end{bmatrix}\right)\]

But what if we want to do this more than once? What if this sequence of transformations is used often? Is it efficient to multiply every vector twice each time?

No, it’s not. Instead, we do this:

\[\left(\begin{bmatrix}-1 & 1 \\ 0 & -2\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}-1 & -1 \\ 1 & -1\end{bmatrix}\right)\begin{bmatrix}1 \\ 1\end{bmatrix}\]

So simple, but so mindblowing at the same time. What does this product of matrices give us?

\[\begin{bmatrix}-1 & 1 \\ 0 & -2\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}-1 & -1 \\ 1 & -1\end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix}2 & 0 \\ -2 & 2\end{bmatrix}\]

Hmm, still looks like a set of basis vectors to me.

That’s because it is. It gives us the position of our basis vectors after the application of both transformations, from right to left (the transformation on the right is applied first, as we saw when we first multiplied it with the vector).

Let’s see how we calculated this.

The calculation

Onto the mechanical part now. Let’s try to understand what goes on inside a matrix to matrix multiplication. This is what we had, right?

\[\begin{bmatrix}-1 & 1 \\ 0 & -2\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}-1 & -1 \\ 1 & -1\end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix}2 & 0 \\ -2 & 2\end{bmatrix}\]

Do you remember what happens during a matrix to vector multiplication? If yes, I have some good news for you. Guess what’s inside a matrix?

That’s right, two vectors.

What we do is the matrix to vector multiplication, but twice. For both vectors contained inside the matrix. Here’s how it looks like:

\[\begin{bmatrix}-1 & 1 \\ 0 & -2\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}-1 & -1 \\ 1 & -1\end{bmatrix}=\overbrace{-1\begin{bmatrix}-1 \\0\end{bmatrix}+1\begin{bmatrix}1 \\-2\end{bmatrix}}^{\text{first column}},\ \overbrace{-1\begin{bmatrix}-1\\0\end{bmatrix}-1\begin{bmatrix}1\\-2\end{bmatrix}}^{\text{second column}} \\ =\begin{bmatrix}1+1 & 1-1 \\ 0-2 & -2+2\end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix}2 & 0 \\ -2 & 2\end{bmatrix}\]

Inverse of a matrix

So a matrix is a transformation. Cool. But what if we want to undo a transformation we apply? That’s where the inverse comes into play.

An inverse of a matrix is another matrix that reverses the transformation the original matrix applies.

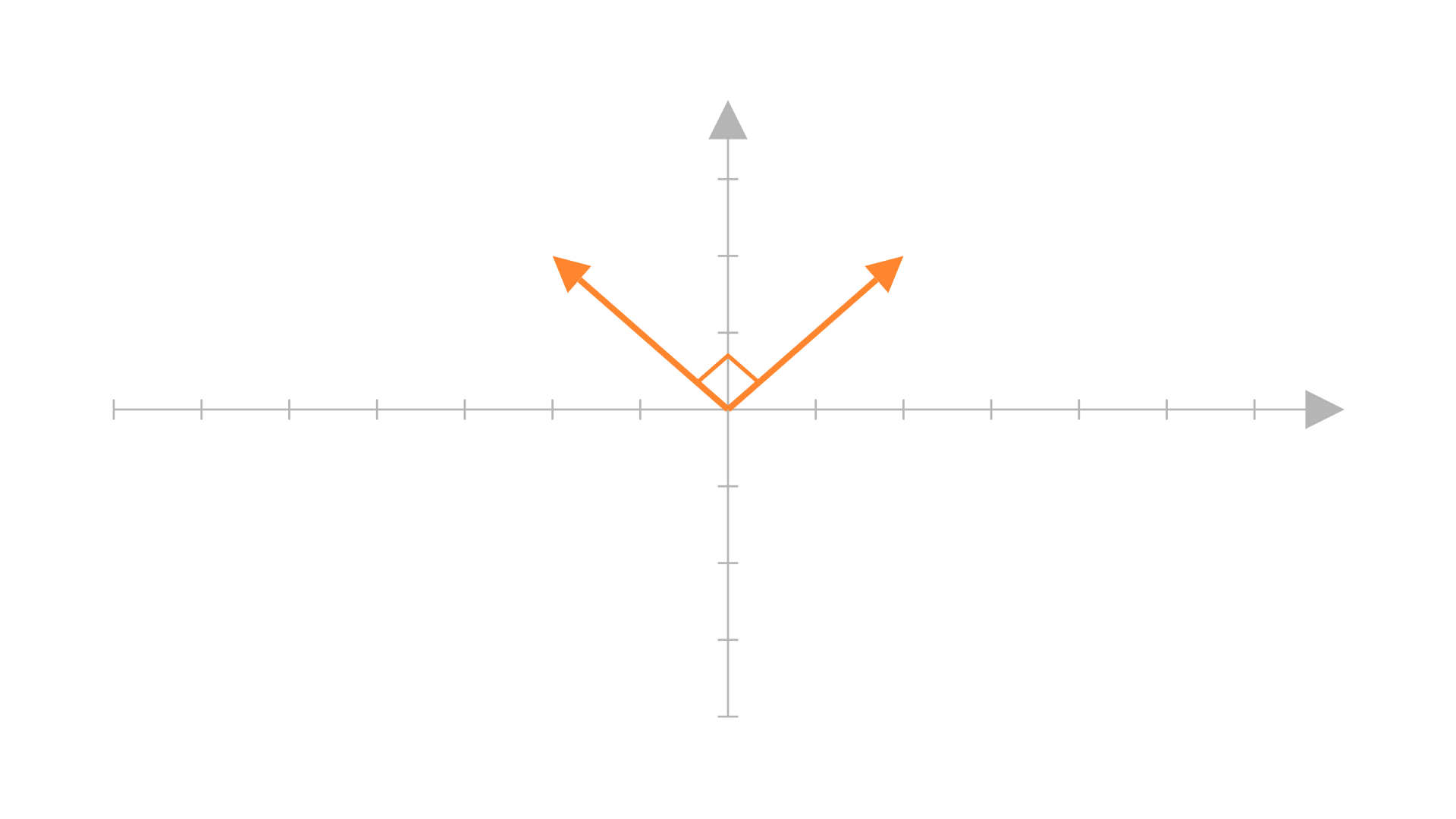

For example we have a matrix \(\boldsymbol{A}=\begin{bmatrix}0 & -1 \\ 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix}\) that does this:

Then, the inverse of this matrix \(\boldsymbol{A}^{-1}\) will be a transformation:

Guess what happens when we apply this matrix to a space transformed using \(\boldsymbol{A}\):

There’s another property of the inverse that makes sense when you think about it in terms of transformations. Just like: \[8\times\frac{1}{8}=1\]

The matrix equivalent of this can be thought of as: \[\boldsymbol{A}\boldsymbol{A}^{-1}=\boldsymbol{A}^{-1}\boldsymbol{A}=\boldsymbol{I}\]

The analogy is not 100% correct, because we can’t divide by a matrix. But \(\boldsymbol{A}^{-1}\) is the reciprocal of \(\boldsymbol{A}\) in the sense it reverses the transformation applied by \(\boldsymbol{A}\). The intuition for this was what you saw in the animation above. When you combine (i.e. multiply) a matrix with its inverse, both transformations cancel each other out, leaving behind a special matrix equivalent to \(1\) in matrix multiplication.

Identity matrix

The \(\boldsymbol{I}\) we saw in the previous section is what we call an identity matrix. Multiplying any matrix or vector by an identity matrix will result in no change at all.

An identity matrix consists of \(1\)s along its main diagonal (i.e. where the row number and column number are the same. Example: \(\boldsymbol{A}_{2, 2}\)) and \(0\)s everywhere else.

For example, a \(2\times 2\) identity matrix would be something like this: \(\begin{bmatrix}1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1\end{bmatrix}\).

A \(3\times 3\) identity matrix would be \(\begin{bmatrix}1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1\end{bmatrix}\).

If you look closely at the matrix, you will realize why it amounts to no transformation whatsoever. (Hint: Look at the basis vectors it holds).

But it holds the original basis vectors right? \([1,\ 0]\) and \([0,\ 1]\) are \(\hat{i}\) and \(\hat{j}\). So multiplication by an identity matrix should transform any space back to our default vector space.

Not exactly. This is where a change of perspective is important.

In a transformed space, we represent all vectors with the corresponding basis vectors, right? So in that space, the coordinates \([1,\ 0]\) and \([0,\ 1]\) represent those basis vectors themselves! And so, multiplication by \(\boldsymbol{I}\) will result in no change whatsoever, because you multiply them by the coordinates of their basis vectors.

Still confused? Recall this slick animation from the last post. It shows how the coordinates differ in different spaces.

At the end of the day, we need to understand all of these are constructs to help us make sense of things and help us define certain concepts easily. There is no graph in the real world, we made it up. And for convenience, we choose the default values of \(\hat{i}=[1,\ 0]\) and \(\hat{j}=[0,\ 1]\).

Nobody’s stopping us from picking \(\hat{i}=[-1, 1]\) and \(\hat{j}=[0, 2]\). And these coordinates are different because we look at them from the perspective of the default values we chose. What if we just chose these points as our default? Then they would be our \([1,\ 0]\) and \([0,\ 1]\).

BTW: Identity matrices are always square, i.e the number of rows will always be equal to the number of columns.

Transpose

Another operation we perform on matrices and vectors is called the transpose. A transpose is when we swap the row elements and the column elements of the matrix. Transpose of a matrix \(\boldsymbol{A}\) is given by \(\boldsymbol{A^{\top}}\), and \(\boldsymbol{A^{\top}}\) is defined as:

\[\boldsymbol{A^{\top}}_{i,j}= \boldsymbol{A}_{j,i}\]

So, transpose of a matrix \(\begin{bmatrix}1&2\\3&4\end{bmatrix}\) would be \(\begin{bmatrix}1&3\\2&4\end{bmatrix}\).

Similarly, transpose of \(\begin{bmatrix}1&2&3\\4&5&6\\7&8&9\end{bmatrix}\) is \(\begin{bmatrix}1&4&7\\2&5&8\\3&6&9\end{bmatrix}\).

You can think of vectors as matrices with a unit dimension. For example, \([1,\ 1]\) is a vector with dimensions \(1\times 2\) and \(\begin{bmatrix}1 \\ 1\end{bmatrix}\) is a vector with dimensions \(2\times 1\).

(Remember, it’s \(\text{rows}\times\text{columns}\)).

So, the transpose of \([1,\ 1]\) is \(\begin{bmatrix}1 \\ 1\end{bmatrix}\).

Unfortunately, at this point, I’m not sure what the transpose implies, or why we do it apart from computational ease (at least in the case of deep learning). So it will be difficult for me to explain it here. All the answers I found were either not intuitive explanations, or too complicated for me to present here with the amount of base knowledge I have provided (and built myself) until now. In case you want to do some extra reading, you’re free to look at this Quora thread.

Broadcasting

Another convenient operation we do on vectors is something called broadcasting a vector. (As far as I know, this is specific to deep learning and the frameworks we use to write DL code in).

With broadcasting, we can add a vector to a matrix. What happens is we create a matrix where each row is the same vector copied over and over. An example should help clear it up.

For example, we want to add \([1,\ 1]\) to the matrix \(\begin{bmatrix}1&2\\3&4\end{bmatrix}\). So what we do is this:

\[\begin{bmatrix}1&2\\3&4\end{bmatrix}+\begin{bmatrix}1&1\\1&1\end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix}2&3\\4&5\end{bmatrix}\]

In mathematical notation, \(\boldsymbol{C}=\boldsymbol{A}+\boldsymbol{b}\) is notational shorthand for what you see above. Whenever you see something like \(\boldsymbol{A}+\boldsymbol{b}\), that’s broadcasting in action.

BTW: Matrices are generally represented by bold capital letters, and vectors are represented by bold lowercase letters. For example, \(\boldsymbol{M}\) is a matrix and \(\boldsymbol{v}\) is a vector.

Hadamard product

This is the product you originally think of when you think of multiplying matrices.

Also called element-wise product, the Hadamard product of two matrices is the product of every element in the first matrix with the corresponding element in the second matrix. (Denoted by \(\boldsymbol{A}\odot\boldsymbol{B}\)).

For example, the element-wise product of \(\begin{bmatrix}1&2\\3&4\end{bmatrix}\) and \(\begin{bmatrix}2&2\\2&2\end{bmatrix}\) is:

\[\begin{bmatrix}1&2\\3&4\end{bmatrix}\odot\begin{bmatrix}2&2\\2&2\end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix}1\times2&2\times2\\3\times2&4\times2\end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix}2&4\\6&8\end{bmatrix}\]

Apart from deep learning, this is used in lossy compression algorithms like JPEG (Source: Wikipedia).

Trace

The trace of a matrix is the sum of all the elements on its main diagonal. It is formally defined as:

\[\text{Tr}(\boldsymbol{A})=\sum_i{\boldsymbol{A}_{i,i}}\]

For example, the trace of \(\boldsymbol{B}=\begin{bmatrix}1&2&3\\4&5&6\\7&8&9\end{bmatrix}\) is given by:

\[\text{Tr}(\boldsymbol{B})=1+5+9=15\]

Again, an attempt to find answers about the trace had me run into the same problems as with the transpose. But, if you want something extra to read, the Wikipedia page, this question on the physics StackExchange and this thread on MathOverflow will prove useful.

Some special vectors and matrices

To finish up this matrix section, we will look at some special matrices and vectors we come across often.

Diagonal matrix

A diagonal matrix is a matrix where all off-diagonal entries are zero.

We can denote a square diagonal matrix as \(diag(\boldsymbol{v})\), where \(\boldsymbol{v}\) is a vector containing all the elements of the diagonal of the matrix.

For example, \(diag(\boldsymbol{x})\), where \(\boldsymbol{x}=[1,\ 2,\ 3]\) will be \(\begin{bmatrix}1&0&0\\0&2&0\\0&0&3\end{bmatrix}\).

We’re interested in diagonal matrices because of the following properites:

- To multiply \(diag(\boldsymbol{v})\) with another vector \(\boldsymbol{x}\), we just scale each \(x_i\) by \(v_i\), i.e. \(\boldsymbol{v}\odot\boldsymbol{x}\)

- To find the inverse of \(diag(\boldsymbol{v})\), we take the reciprocal of every entry in \(\boldsymbol{v}\).

BTW: Diagonal matrices are not necessarily square.

Symmetric matrix

A matrix \(\boldsymbol{A}\) is said to be symmetric when \(\boldsymbol{A}_{i,j}=\boldsymbol{A}_{j,i}\).

In simple words, a symmetric matrix is a matrix equal to its transpose.

Unit vector

A vector with magnitude 1.

Here’s what magnitude is if this doesn’t seem familiar.

Orthogonal vectors

Two vectors are said to be orthogonal to each other when their dot product is zero, i.e. \(\boldsymbol{x^{\top}y}=0\).

In a geometric sense, it means these vectors are perpendicular to each other. Something like:

\(\hat{i}\) and \(\hat{j}\) are orthogonal too (well, technically orthonormal as we will see next).

Orthonormal vectors

Two vectors are said to be orthonormal when they are both unit vectors and orthogonal.

So yeah, \(\hat{i}\) and \(\hat{j}\) are orthonormal, not just orthogonal.

Orthogonal matrix

A matrix is said to be orthogonal when the rows and columns are orthonormal vectors.

Please note, the rows and columns have to be orthonormal, not orthogonal.

A striking property of orthogonal matrices is:

\[\boldsymbol{Q}\boldsymbol{Q^{\top}}=\boldsymbol{I}\]

where \(\boldsymbol{Q}\) is an orthogonal matrix.

The logic behind this is pretty simple, and I’m sure you can figure it out on your own.

(Hint: use the fact that rows and columns are mutually orthonormal, see what gets multiplied where. Use the matrix multiplication shortcut here, it’ll be easier to understand)

But this property has a much wilder implication. Because \(\boldsymbol{QQ^{\top}}=\boldsymbol{I}\), it also means:

\[\boldsymbol{Q^{\top}}=\boldsymbol{Q}^{-1}\]

That’s convenient. Calculation of inverses can be computationally painful, but for orthogonal matrices, it’s just their transpose.

Pretty neat, isn’t it?

BTW: Orthogonal matrices are real square matrices. Meaning, all elements are real numbers, and no. of rows have to be equal to the no. of columns.

Tensor

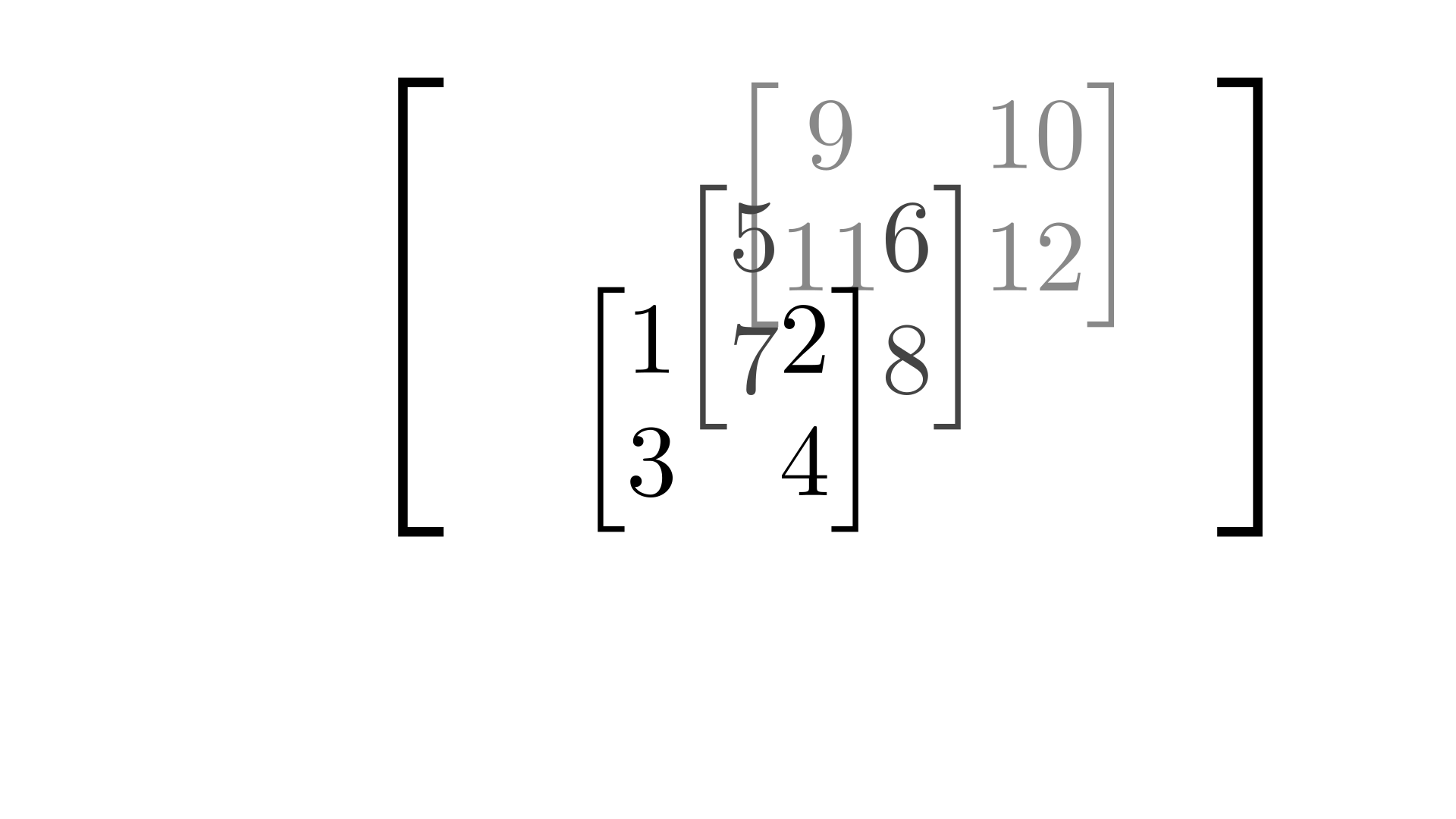

And to finish off this post, we have the object we use most in deep learning, the tensor.

In the context of deep learning, a tensor is a multidimensional generalization of vectors and matrices.

What that means in simple terms is if vectors are \(1\) dimensional and matrices are \(2\) dimensional, then tensors are \(n\) dimensional.

For example,

Vector: \([1,\ 2]\) or \(\begin{bmatrix}1\\2\end{bmatrix}\)

Matrix: \(\begin{bmatrix}1&2\\3&4\end{bmatrix}\)

Tensor: \(\left[\begin{bmatrix}1&2\\3&4\end{bmatrix}, \begin{bmatrix}5&6\\7&8\end{bmatrix}, \begin{bmatrix}9&10\\11&12\end{bmatrix}\right]\)

The tensor given above is 3 dimensional. You can visualize it being 3D by thinking of the three matrices stacked on top of each other, forming something like a cube of matrices.

But good luck trying to visualize it when the dimensions go beyond three.

One quick way to find out how many dimensions the tensor has is to see how many indices we need to reference one element of the tensor. For example, in the above tensor, to get the element \(2\), we need \(3\) indices, i.e. \(\tt{T}_{1, 1, 2}\). The first \(1\) selects the first matrix, the second \(1\) selects the first row of the first matrix, the last \(2\) selects the second column of the first row of the first matrix.

BTW: The machine learning/deep learning definition of a tensor is NOT the same as the original mathematical definition. They’re both different concepts with the only common link being they’re both multidimensional vectors/matrices (or arrays if you’re familiar with them). This is a common theme in deep learning where some of the terminologies we use don’t correspond with actual definitions of where we borrow the idea from.

Here’s the wiki link if you want to read about tensors in mathematics. This video by professor Daniel Fleisch is also helpful.

That pretty much covers most of the basics ideas we need for linear algebra. We are now ready to start with linear systems.

Reality check

If you understood what you read, you should be able to answer the following questions satisfactorily (to whose satisfaction you ask? Yours of course!)

- What happens when we multiply two matrices?

- Why do we perform matrix to matrix multiplication?

- What is an inverse of a matrix? What does it signify?

- What do you mean by an identity matrix?

- What is transpose?

- What do you mean by broadcasting a vector?

- What is a Hadamard product?

- What is the trace operation?

- Why are we so interested in diagonal matrices?

- What is a symmetric matrix?

- When are two vectors orthogonal?

- When are two vectors orthonormal?

- Why are orthogonal matrices so convenient?

- What are tensors? (In the context of deep learning)

Extra references

3Blue1Brown’s Essence of linear algebra series was once again a huge help in gaining the intuition I’ve provided. You should check it out.

All other sources I’ve used have been mentioned throughout as well.

Thanks for reading to the end. See you next time