Linear systems (Prerequisites)

Hey! Welcome back. Now that we’re clear on most of the fundamentals we need, we can start with the real meat of the subject.

Before we dive into linear systems of equations, there are three more terms you should be familiar with. We’ll start with those first.

Linear combinations

I went over this in the first part of the basics. But it’s important enough to deserve an entire section of its own.

So let’s say we have a set of vectors \(\boldsymbol{x}\), \(\boldsymbol{y}\) and \(\boldsymbol{z}\). A linear combination of these vectors would look like:

\[\alpha\boldsymbol{x}+\beta\boldsymbol{y}+\gamma\boldsymbol{z}\]

where \(\alpha\), \(\beta\) and \(\gamma\) are real valued scalars.

Generally speaking, a linear combination of a set of vectors is those vectors each multiplied by some scalar and added together. The formal definition looks something like this:

\[\sum_i{c_i\boldsymbol{v}^{(i)}}\]

where \(\boldsymbol{v}^{(i)}\) is the \(i^{th}\) element of a set of vectors and \(c_i\) is the \(i^{th}\) element of a set of real scalars.

This is useful to determine if a vector is linearly dependent on other vectors or not.

Linear dependence

A vector is said to be linearly dependent on a set of vectors if that vector can be derived from some linear combination of the set.

For example: consider the vectors \(\boldsymbol{a}=[1,\ 1]\), \(\boldsymbol{b}=[3,\ 4]\) and \(\boldsymbol{c}=[4,\ 5]\).

It’s not difficult to see:

\[\boldsymbol{c}=\boldsymbol{a}+\boldsymbol{b}\]

In this case, we say \(\boldsymbol{c}\) is linearly dependent on \(\boldsymbol{a}\) and \(\boldsymbol{b}\).

Why are we so interested in linear dependencies? Because it helps us determine the span of a set of vectors.

Span

Remember when I told you about this? Yeah, we’re going to discuss the complete truth now.

The span of a set of vectors, is the set of all the vectors we can obtain from all possible linear combinations of them.

For example:

Consider the vector \(\boldsymbol{a}=[1,\ 1]\). Since there’s only this one vector, all the linear combinations of this would be \(1\cdotp\boldsymbol{a}\), \(2\cdotp\boldsymbol{a}\), \(3\cdotp\boldsymbol{a}\) and so on. Basically, \(\alpha\cdotp\boldsymbol{a}\) where \(\alpha\in\mathbb{R}\).

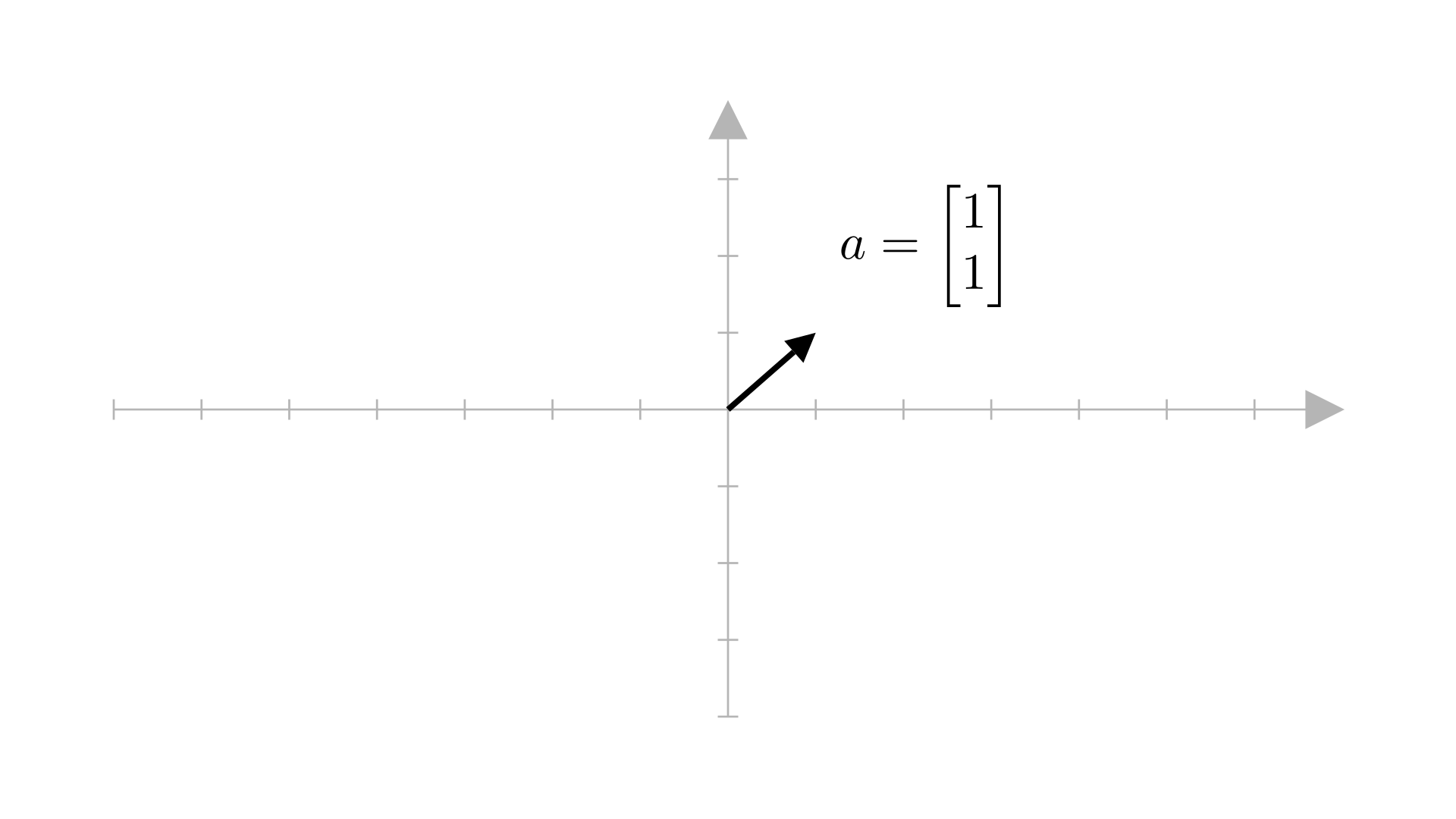

Here’s what \(\boldsymbol{a}\) looks like:

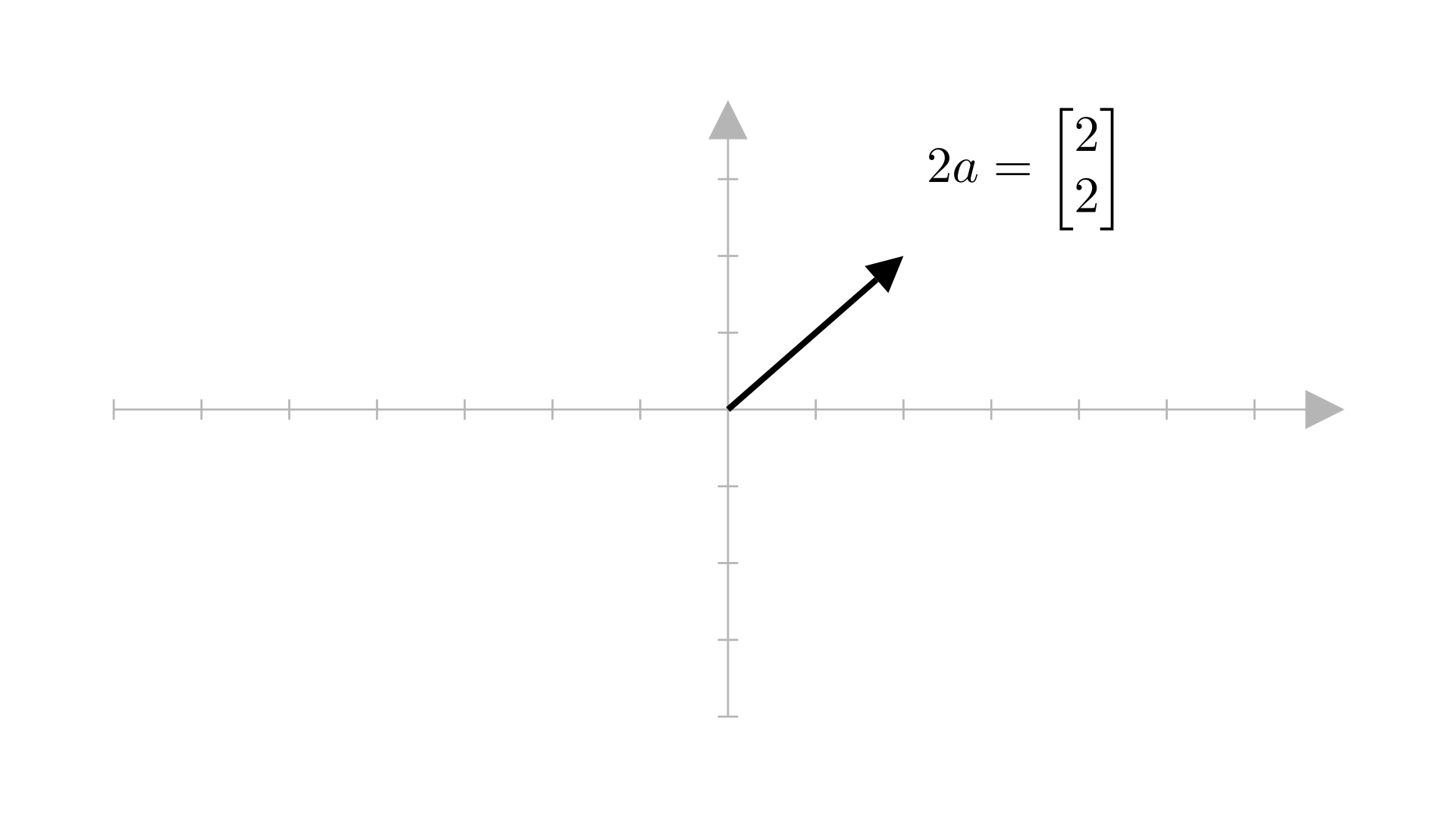

And here’s what \(2\cdotp\boldsymbol{a}\) looks like:

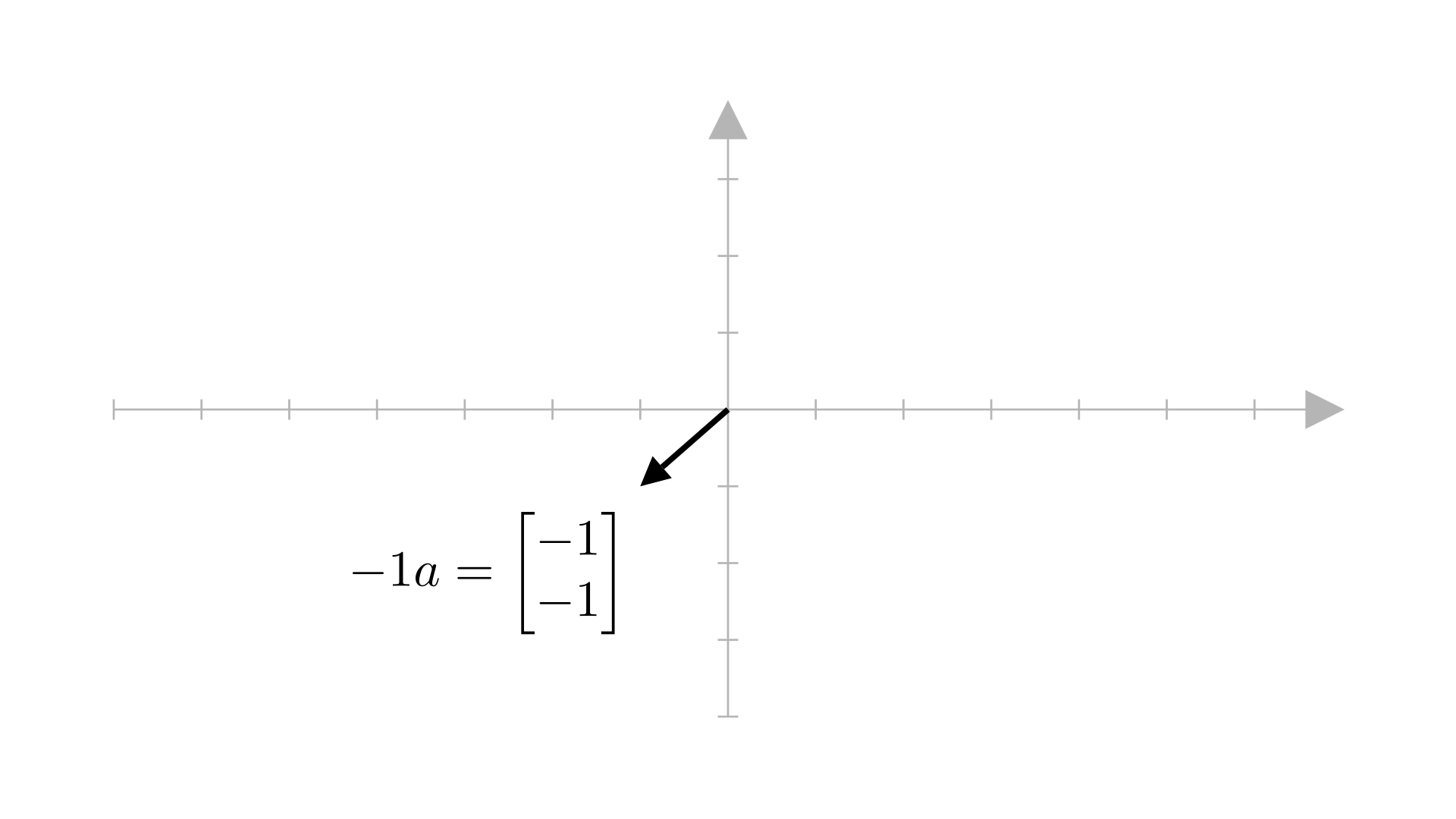

And here’s what \(-1\cdotp\boldsymbol{a}\) looks like:

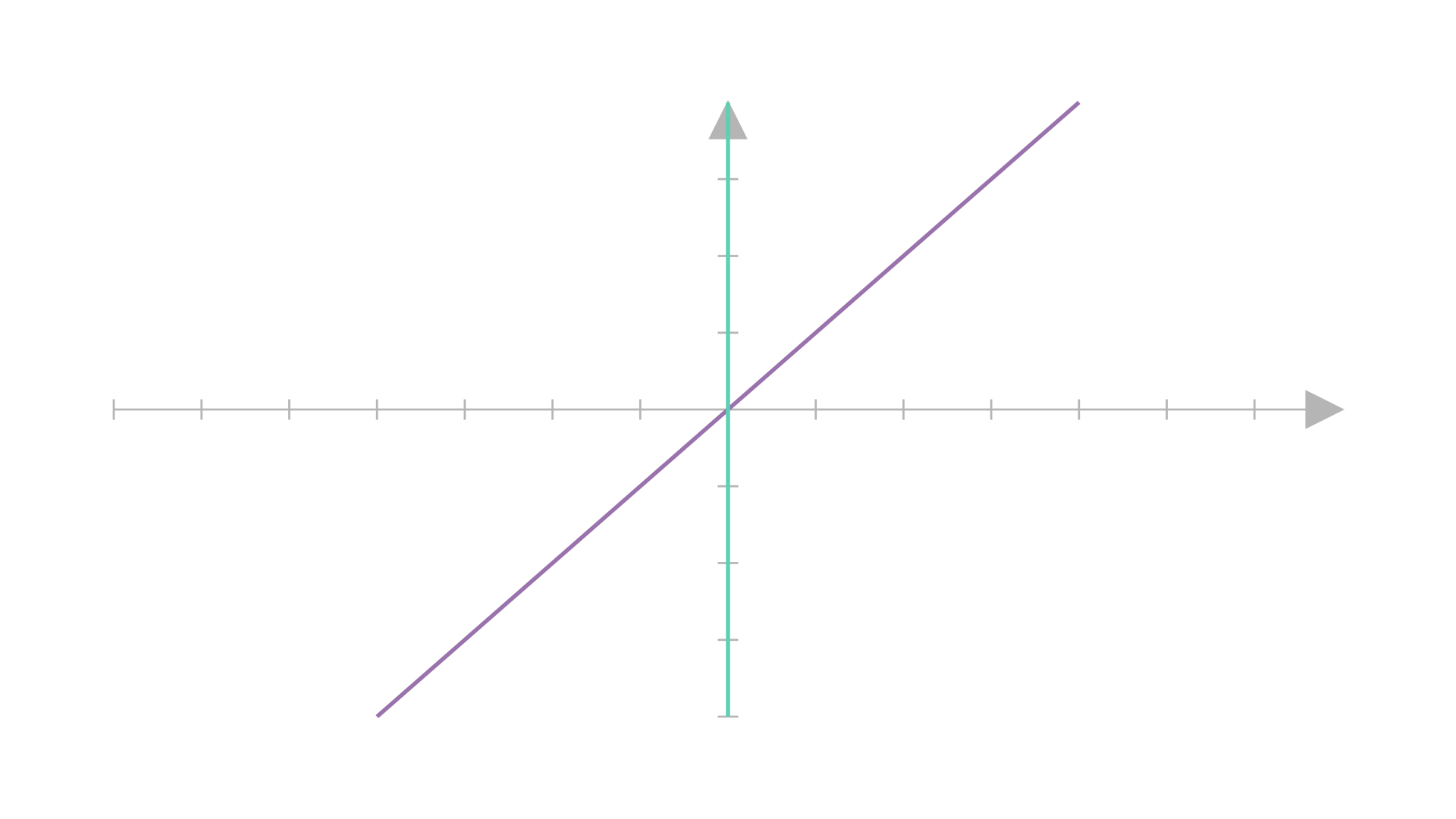

So, the span of \(\boldsymbol{a}\), i.e. \(\alpha\boldsymbol{a}\) for all values of \(\alpha\), looks something like this:

The span of \(\boldsymbol{a}\) is a line. This means that all the possible vectors which we can obtain from \(\boldsymbol{a}\), lie on that line.

(Please note the line is infinite in length, but I can’t animate that.)

The span of a single vector is always a line.

Thus, using one vector, we can trace out a line in space.

Now consider this example:

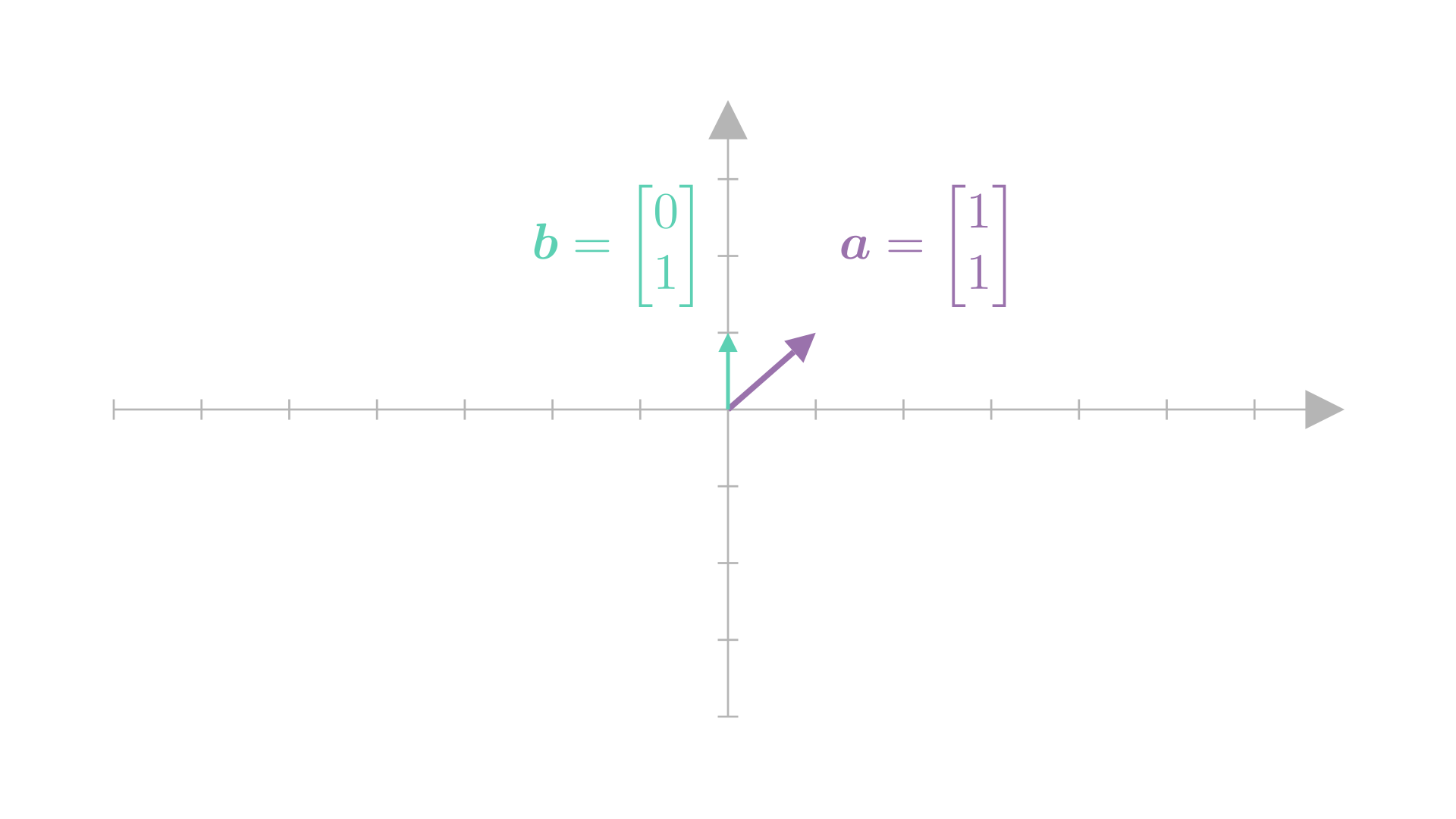

Let our set of vectors be \(\boldsymbol{a}=[1,\ 1]\) and \(\boldsymbol{b}=[0,\ 1]\).

Here’s what they look like:

By definition, the span would be the set of all possible linear combinations of \(\boldsymbol{a}\) and \(\boldsymbol{b}\), i.e. \((\alpha\boldsymbol{a}+\beta\boldsymbol{b})\) where \(\alpha,\ \beta\in\mathbb{R}\).

No harm in visualizing the points we obtain from different combinations, right?

Consider the combination \(\alpha=1\) and \(\beta=1\):

\(\alpha=-1\) and \(\beta=1\):

\(\alpha=1\) and \(\beta=-1\):

and \(\alpha=-1\) and \(\beta=-1\):

As you can see, using these two vectors, we can move in two directions now. We can go in the directions of both \(\boldsymbol{a}\) and \(\boldsymbol{b}\).

And by this logic, it is reasonable to conclude we can obtain every single vector in this 2D plane using linear combinations of \(\boldsymbol{a}\) and \(\boldsymbol{b}\). (You’re free to try out every combination manually :P)

Thus, the span of \(\boldsymbol{a}\) and \(\boldsymbol{b}\) is the entire 2D plane.

Another way to think of it could be in terms of the spans of \(\boldsymbol{a}\) and \(\boldsymbol{b}\), which look like:

Because we only had \(\boldsymbol{a}\)’s span before, we could only move along that line. Now we have \(\boldsymbol{b}\)’s span, so we can move \(\boldsymbol{a}\)’s span along \(\boldsymbol{b}\)’s, thus yielding all the points covered.

(P.S. Both those lines are infinitely long, but I cannot animate infinitely long lines. So imagine those lines extend way further and thus, cover the entire 2D plane)

We can extend this logic to any \(n\) dimensional vectors. Using \(n\) vectors in an \(n\) dimensional space, we can trace out the entire space using linear combinations of these \(n\) vectors.

Okay but why does linear dependence matter?

Where does linear dependence come in the picture here as I told you in the last section?

Let’s say we have two vectors in the 2D plane, \(\boldsymbol{p}=[1,\ 1]\) and \(\boldsymbol{q}=[2,\ 2]\).

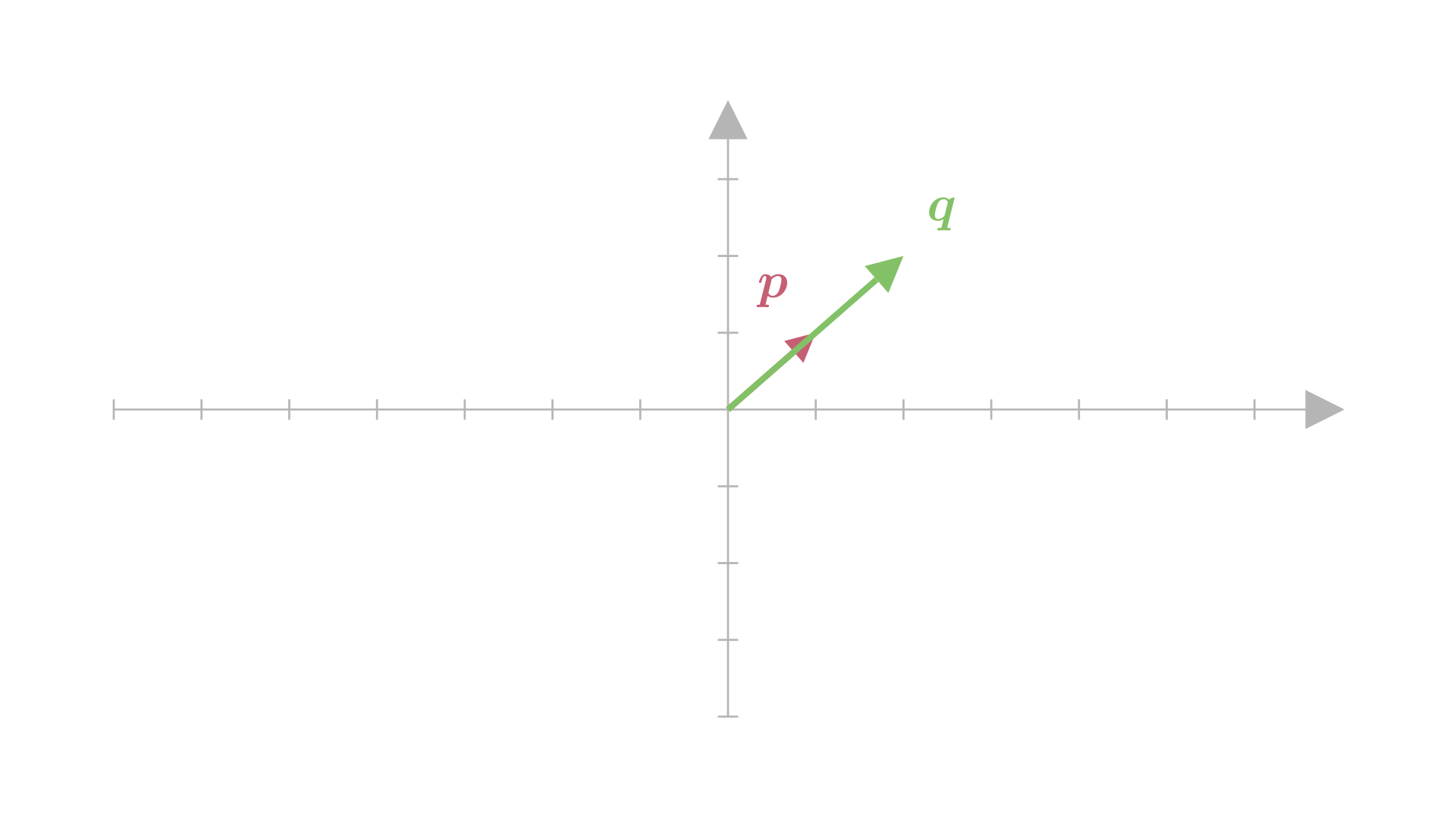

Ideally, we can trace the entire 2D plane using two vectors, but let’s take a look at these two:

See the problem? \(\boldsymbol{q}\) already lies on the span of \(\boldsymbol{p}\). And therefore will not contribute any new vectors in the span.

In other words, \(\boldsymbol{q}\) is linearly dependent on \(\boldsymbol{p}\).

\[\boldsymbol{q}=2\boldsymbol{p}\]

Let’s take another example:

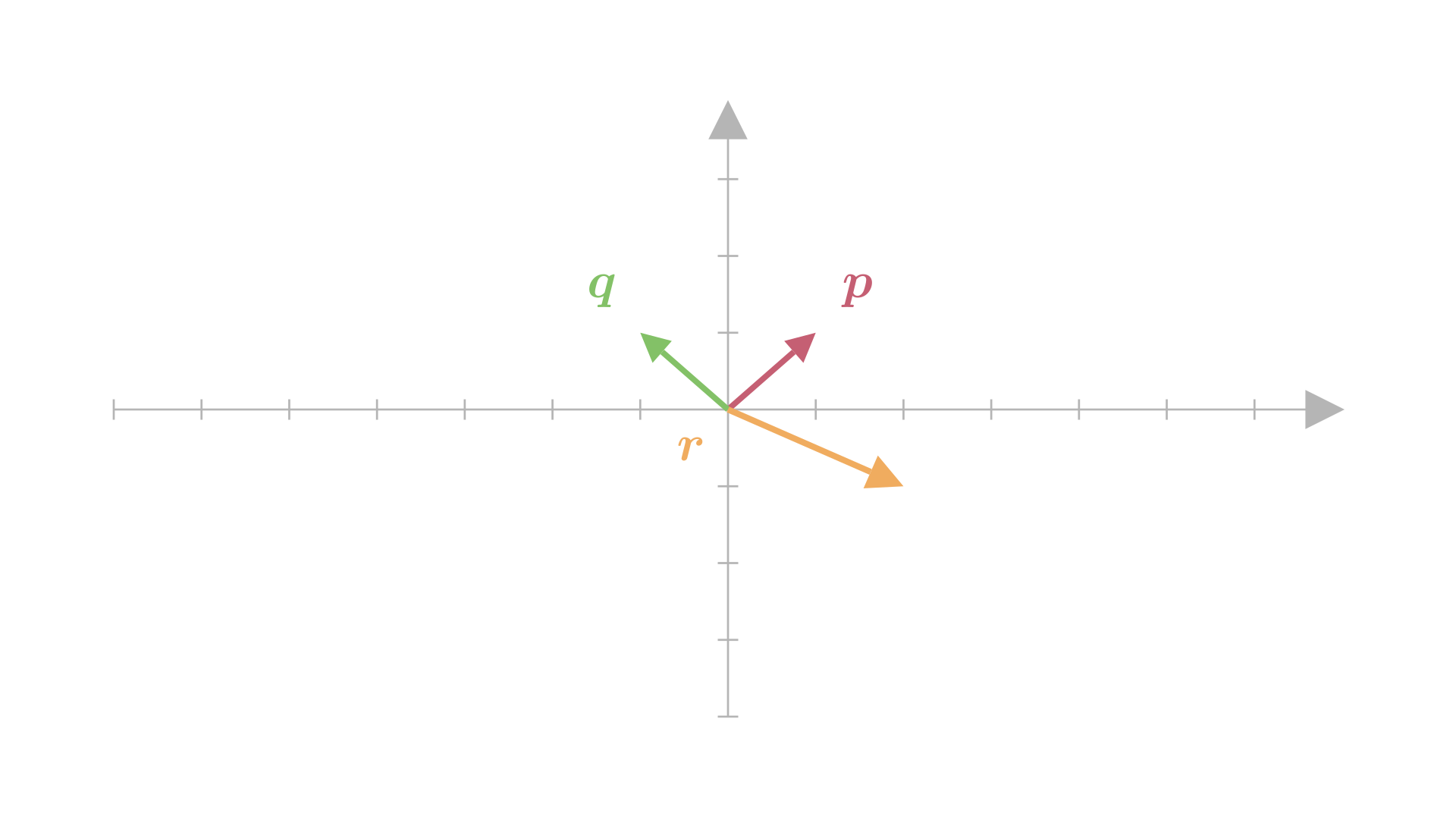

Consider the vectors \(\boldsymbol{p}=[1,\ 1]\), \(\boldsymbol{q}=[-1,\ 1]\) and \(\boldsymbol{r}=[2,\ -1]\).

If you think about it a little:

\[\boldsymbol{r}=\frac{1}{2}\boldsymbol{p}-\frac{3}{2}\boldsymbol{q}\]

➢ Click here to see how I came up with \(\frac{1}{2}\) and \(\frac{3}{2}\).

Because I want a linear combination of \(\boldsymbol{p}\) and \(\boldsymbol{q}\) to equal \(\boldsymbol{r}\), I start with this equation: \[\boldsymbol{r}=a\boldsymbol{p}+b\boldsymbol{q}\] I substitute the values I have: \[\begin{aligned}\begin{bmatrix}2\\-1\end{bmatrix} &= \begin{bmatrix}a\\a\end{bmatrix}+\begin{bmatrix}-b\\b\end{bmatrix} \\ \begin{bmatrix}2\\-1\end{bmatrix} &= \begin{bmatrix}a-b\\a+b\end{bmatrix}\end{aligned}\] Now we equate the individual elements of these vectors: \[\tag{1}2=a-b\] \[\tag{2}-1=a+b\] Add equations \((1)\) and \((2)\). We get: \[\begin{aligned}1 &= 2a \\ \implies a &= \frac{1}{2}\end{aligned}\]Plug this value of \(a\) in the other equation to get \(b\).

Since \(\boldsymbol{r}\) is linearly dependent on \(\boldsymbol{p}\) and \(\boldsymbol{q}\), it won’t contribute any new vectors to the span.

This brings us to the following conclusion: To trace out an \(n\) dimensional space using \(n\) vectors, all those \(n\) vectors must be linearly independent.

I wanted to finish the entire topic in one go, but I realized it would make this post very lengthy. So I’ve decided to break it into two parts.

Next time, we’re going to look at how systems of linear equations are represented in linear algebra, and the conditions necessary to solve the system. We will also see when a matrix can have an inverse, and when it cannot.

Reality check

If you understood what you read, you should be able to answer the following questions satisfactorily (to whose satisfaction you ask? Yours of course!)

- What do you mean by a linear combination?

- When is a vector linearly dependent on others?

- What is span?

- How does linear dependence affect span?

- How many vectors would you need to trace out the entire 3D space?

Thanks for reading to the end. See you next time.